In advance of a Madison DSA event, Building the Union Without Permission, Monday February 1st at 6:30pm, Frank Emspak spoke with Angaza Laughinghouse, member of North Carolina Public Services Union and veteran of black liberation, anti-imperialist, and workers’ rights struggles. Angaza details his work building the union and explains its development through the Black Workers for Justice.

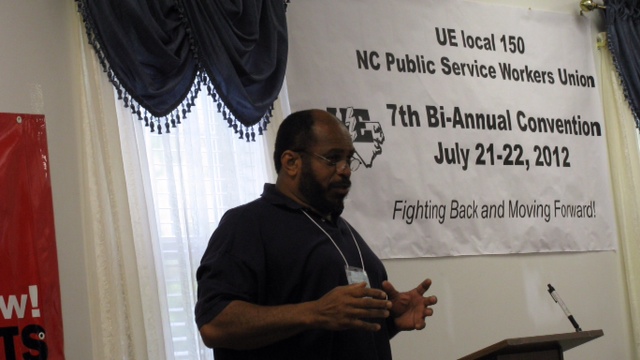

Angaza Laughinghouse: Yes, my name is Angaza Laughinghouse. I’m a founding member of the North Carolina Public Service Workers Union, UE local 150 in North Carolina. And I’m a state worker and I’m just honored to have an opportunity to share our story.

Frank Emspak: Do you have a position now with the local?

Angaza Laughinghouse: Yes, I’m on the political action committee. I’m the chair. I’m also a chair of the rank and file members organizing committee since, our union is ran by the rank and file, we don’t have any staff for our particular chapter. Matter of fact, we have one staff person for the entire state where we have members in 16 locations and, tens and tens of chapters. That means we’re basically ran by the actual members, take up responsibilities inside our local union.

Frank Emspak: Wow. How many people were in the local?

Angaza Laughinghouse: Well, we have over just short, maybe a 4,000 members right now, as you know, what’s pretty challenging to keep members in the midst of what’s going on right now with the pandemic lay offs and lack of revenues coming into cities and state governments. So close to 4,000.

FE: Are these all public sector workers?

AL: No, our union consists of also private sector workers, particularly those that work at Rocky Mount engine plant in the Tarboro-Rocky Mount area. These are workers that make engine parts for the Cummings engine company. And as you know, lots of the auto industry is relocated here in the South. And also lots of the parts are made here in North Carolina.

FE: That’s really amazing. Well, North Carolina has a law that prohibits collective bargaining in the public sector. Is that accurate?

AL: Yes, this is part of the legacy of Jim Crow laws, at a time when most the voting population could not vote. As you know, that was African Americans due to the Jim Crow laws that denied us that basic fundamental human right to vote. They passed a piece of legislation that denied all public sector workers, state, county, city workers, the right to collectively bargain. Initially, they claimed that we didn’t even have a right to organize a union, but it was challenged in the courts and it went way to the Supreme Court.

So in the late 1950s, when they did pass this law, it was later on challenged … And we won at least the recognition of our first amendment, right to freedom of association, free speech, file petitions and grievances against the government. So we were able to organize unions despite this attempted ban on unions and collective bargaining. Right now we only have section 95, 98 of the North Carolina general statute, which denies us this fundamental, right, which is internationally recognized by the UN international labor organization, the right to collectively bargain, which we’re still fighting for.

FE: So under these circumstances, how did the union get started?

AL: Well, I think it’s fair to say that Black Workers for Justice, an organization founded in 1981, 1982, was instrumental in helping build what we call workplace committees. This organization, it’s an organization of black workers that believed that we had to build power, not only in our own communities, black communities in Eastern North Carolina or in the black belt regions of the South, but we had to also build power in the workplace where many of us worked in some of the worse jobs you would … when you could ever think of some of the lowest paying jobs. So, we decided that it was important to build workplace committees.

Black Workers for Justice, building workers, [built a fairness campaign] back in the early 1980s, where we began to build workplace committees, including at the City of Durham, City of Raleigh, some city governments, and also, we encouraged the organizing of state workers in various agencies.

And at first we were just workplace organizations that created what we call the North Carolina Public Service Workers network. It was a network of public sector workers. And we held an assembly at North Carolina Central University way back in 1990. The network decided to formally create an organization which became the North Carolina Public Service Workers organization. This consisted of workers in the North Carolina Department of Transportation, municipal workers from Asheville, Raleigh, Durham, Rocky Mount, and a host of other cities, but that began the basis for us to launch another campaign, which we called [the] “organize the South campaign”, where we actually began to actually send our members in little vans and busloads on a tour to the Northeast, Midwest, even the West coast to learn more about unions, since unions wasn’t something readily understood or had been the experience of many of the workers that we were organizing in these workplaces.

FE: So this is 1992 or so?

AL: Yes, this is the early 1990s. We were able to use it the tour as a way to educate our workers here in the South, and also educate workers in the about the need to do more union organizing in the South. This attracted the attention of many rank and file union leaders who brought it to the attention of their national union leaders that this group of workers in a couple of van loads of workers who were touring and speaking. And, also performing since we had a singing group called the Fruit of Labor singing ensemble that composed and written songs about labor, we were able to bring attention to the need to organize workers in the South.

FE: Like that was sort of like the Freedom Singers from SNCC.

AL: That’s right. Music is a good way to bring a message and bring a fighting spirit to people. So. we brought our fighting spirit from the South to the North and Midwest and West coast, as we attracted the attention of not only the regional and local leaders, but also ultimately the national union leaders and the United steelworkers union, the American Federation of State County, Municipal employees, the Service Employees International Union, the Communication Workers of America and a host of other unions.

FE: Well, how did you pick the UE? I mean that, of all those unions, UE is the smallest one.

AL: Well, I think it’s very important to understand that the unions didn’t pick us. We pick them based on their politics, based on this rank and file social movement unionism, which we’re strong believers of that humans can’t just be workplace organizations. They gotta become come a part of a social movement that takes on many of the issues of a working class people.

So, we decided that we wanted the union that had what we thought was the sharpest politics. And it was willing to also sit with the workers that we were organizing as equals to figure out what would be our plan for broadening out and deepening our union organizing here in North Carolina and later on throughout other Southern States, such as Virginia and West Virginia. We were always pushing the need to organize Southern, local.

Right after we organized UE 150, here in North Carolina, our national union took on organizing the Virginia workers into Local 160 UE. That became a continuing part of our program, which was they organized more unions, here in the South. And, we knew that UE would answer the call right now. We’re organizing workplaces at a meat rendering plant – Valley protein in Fayetteville, [Arkansas]; Valley Proteins has facilities in four other States: in South Carolina, Virginia, North Carolina. So we’re digging in and we know it’s a long protracted struggle, and we don’t necessarily have collective bargaining in these areas.

FE: That’s my next question, how do you bargain in a situation where collective bargaining law says you can’t collectively bargain? Obviously the private sector is another question, but in the public sector, how do you do it?

AL: Well, it’s the private sector too. We have what we call pre-majority unions where we don’t have any formal collective bargaining rights, but we do have shop floor power, and we earned our advances through shop floor action. Gotta have some rank-and-file shop floor action. That’s where the rubber meets the road. When the workers are challenging the bosses right there in the plant. So we do have private sector unions, in our local and UE, that we call pre-majority unions that don’t have collective bargaining, but they still are able to make advances.

For example, in the Rocky Mount engine plant, near Rocky Mount-Tarboro, North Carolina, workers were able to fight to increase their wages. They fought, filed, use the National Labor Relations Act concerted action provision to be able to wear their union caps and buttons union t-shirts in the workplace, even though the bosses initially said no, but we use what we have available through OSHA, The Fair Labor Standards Act, through our political power and community power, to win things.

We were fighting for a paid [Martin Luther] King holiday in this plant. [W]e circulated petitions in the local churches and then the community, and we built alliances with other community organizations, and we were able to win a paid King holiday there at the Rocky Mount engine plant. No need to say that we were able to do the same in the public sector by using shop floor action. And don’t forget too [it is illegal] to strike. I think that we’ve had about three strikes in the public sector. They were illegal, but we did still struck positions with that.

FE: Yes, I understand. I understand the concept there.

AL: Yeah. In Raleigh we struck; in Durham workers struck; Rocky Mount, Greenville workers have taken determined acts and forced the bosses to meet with us. We call it “meet and confer”, not collective bargaining, but meet and confer is something that we can fight for and win in the public and private sectors in order to sit in, to use another form, to really negotiate or try to move forward our agenda and meet the needs of our workers.

FE: And people can pay dues, independently. There’s no checkoff, right? They’re having you work out some dues collection system. I’m sure.

AL: Come on- we’re very creative. In some instances, we even get the cities by getting them to give us the payroll deduction check off by pushing them if they can give the United Way check off. If workers can get United Way check off it’s out of their paychecks. If they can get insurance, if they can get other non-profits to take withhold their dues or their donations, we forced them to do the same in all of the cities that we have built strong union chapters in.

FE: Very interesting. So let me see if I understand it here. You’ve used the pre-majority notion to enter into discussions at the shop floor and if possible, to meet and confer with the larger entity, the company or the administration, and using that system because you have shop floor support, you’ve been able to accomplish a number of things and depending on where a health and safety improvements, improvements in wages, win a Martin Luther King holiday, and other types of gains, is that right?

AL: We’ve even won hazardous pay. And during the pandemic, by using the same sort of shop floor action, building alliances in the community to build public opinion, we’ve won also a worker’s bill of rights ordinance in Durham by building what we call workers’ assemblies of other workers and community folks working with our unit, we’re able to win many things, but we have to be very creative and understand the power of the workers in the workplace shop floor action, and also the importance of building what we call a community0labor alliance or community support, you know, to unite organizations in our community.

Angaza Sababu Laughinghouse, a 40 year plus veteran “social justice trade unionist”, Black freedom fighter, labor and community organizer, shows no signs of retiring. He is presently serving workers as president of the North Carolina Public Service Workers Union, United Electrical ,Machine & Radio (U.E.) Local 150. As an organizer, activist and advocate Angazahas been fighting for the workers’ rights for more than four decades.